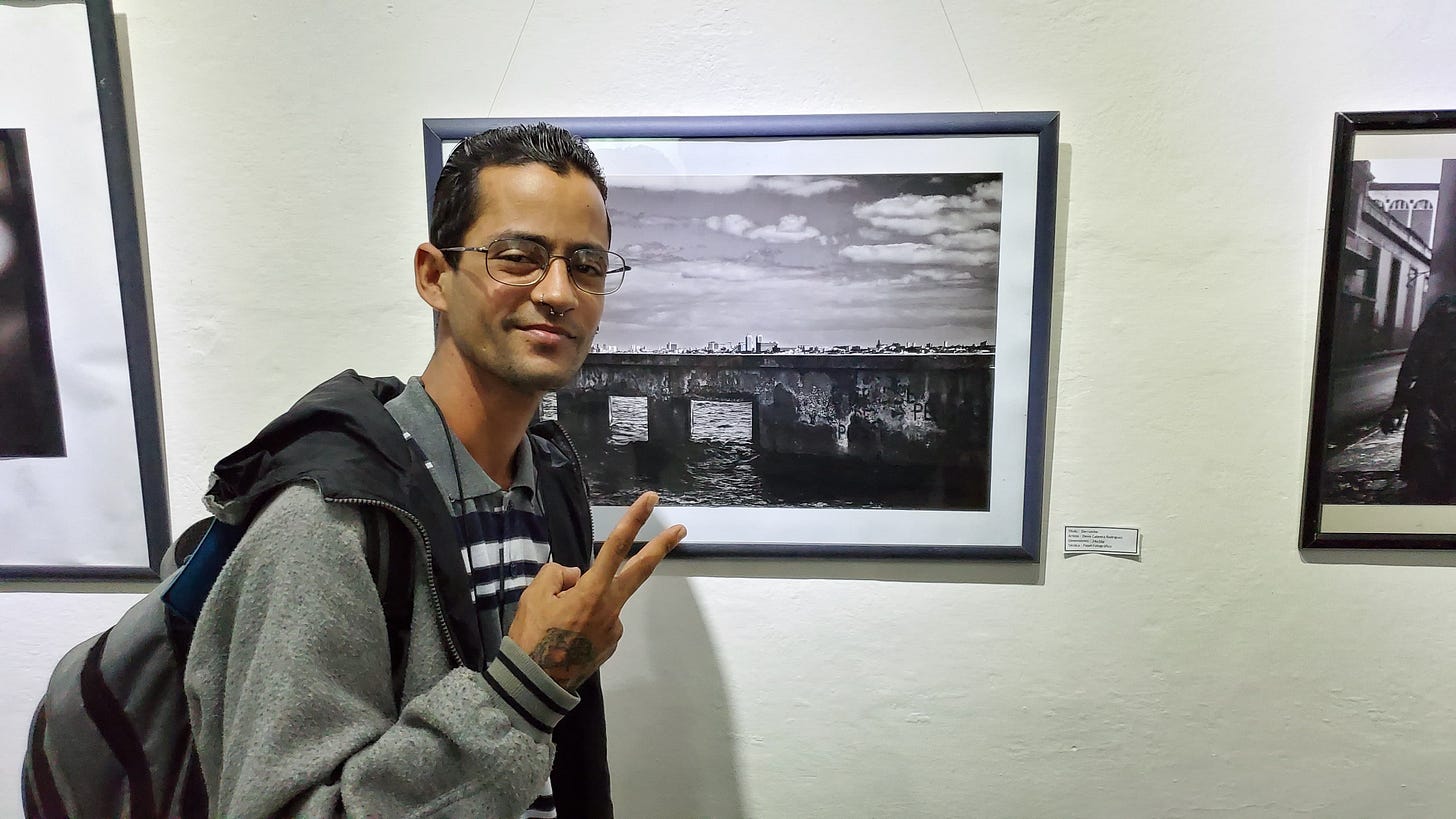

DENIS CABRERA RODRÍGUEZ AND THE COST OF BEING SEEN

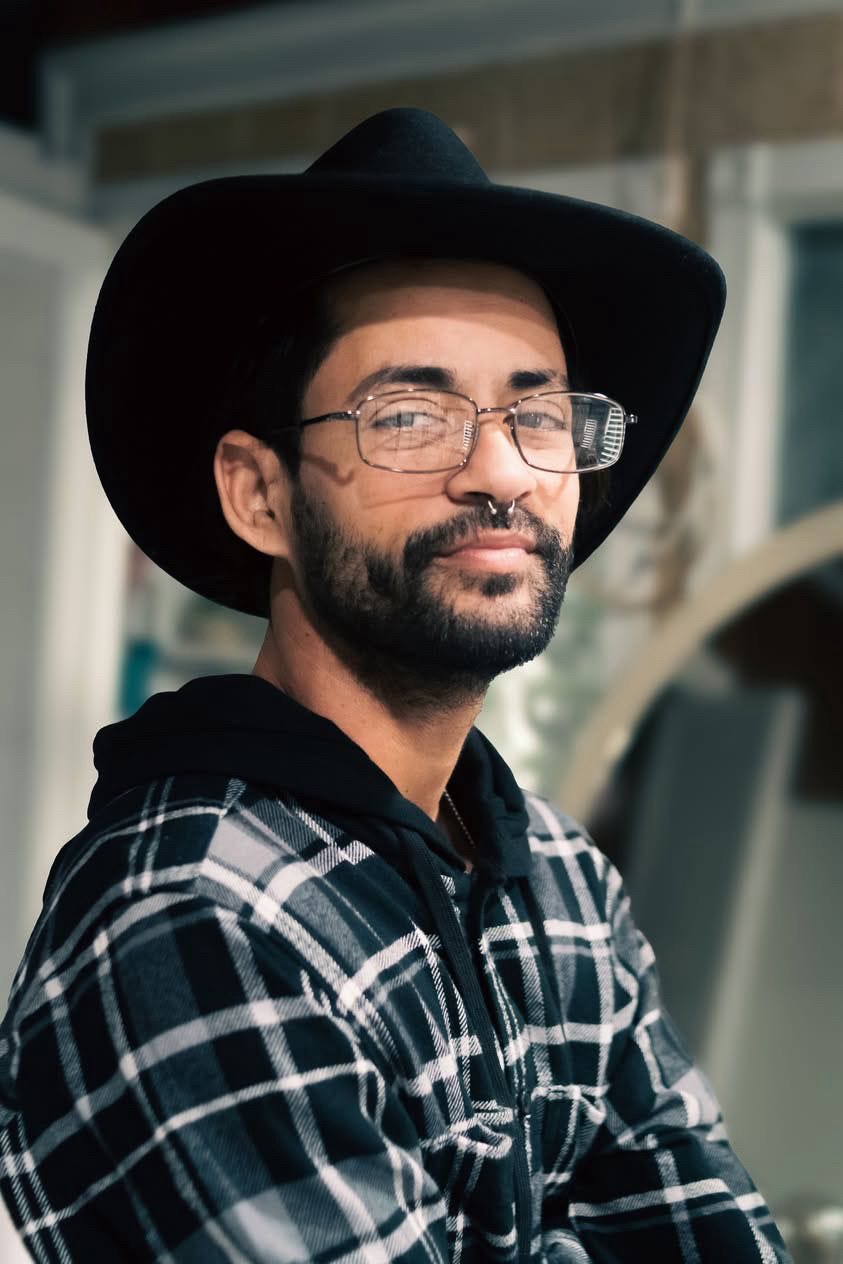

Before he was a detainee number, before he was a medical liability shuffled between concrete walls and emergency rooms, Denis Cabrera Rodríguez was a man who paid attention. He was a photographer in Cuba, drawn to ordinary people and unguarded moments, documenting daily life with the quiet insistence of someone who believes that showing the truth matters. He was not loud. He did not posture. He looked, and he kept looking, even when the state did not like what he saw.

That mattered enough for the Cuban government to act. Before Denis left the country, people close to him say his photographs were confiscated by state authorities. His work was taken from him. Not argued with. Not critiqued. Removed. It was a message he understood clearly: your way of seeing is not welcome here.

So Denis fled. He crossed a border not chasing comfort, but safety. He came to the United States seeking asylum, believing that a country that speaks endlessly about freedom would at least protect his life.

Instead, it put his body in danger.

Denis is 33 years old. He is the father of a young daughter who remains in Cuba and depends on him financially. He is engaged to be married. He is also insulin-dependent, living with Type 1 diabetes and related complications that require constant, careful management. His life depends on routine, nutrition, insulin, and timely medical response. For years, he managed that balance. He had to. His survival depended on it.

That balance collapsed after he was detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement while awaiting the outcome of his asylum case.

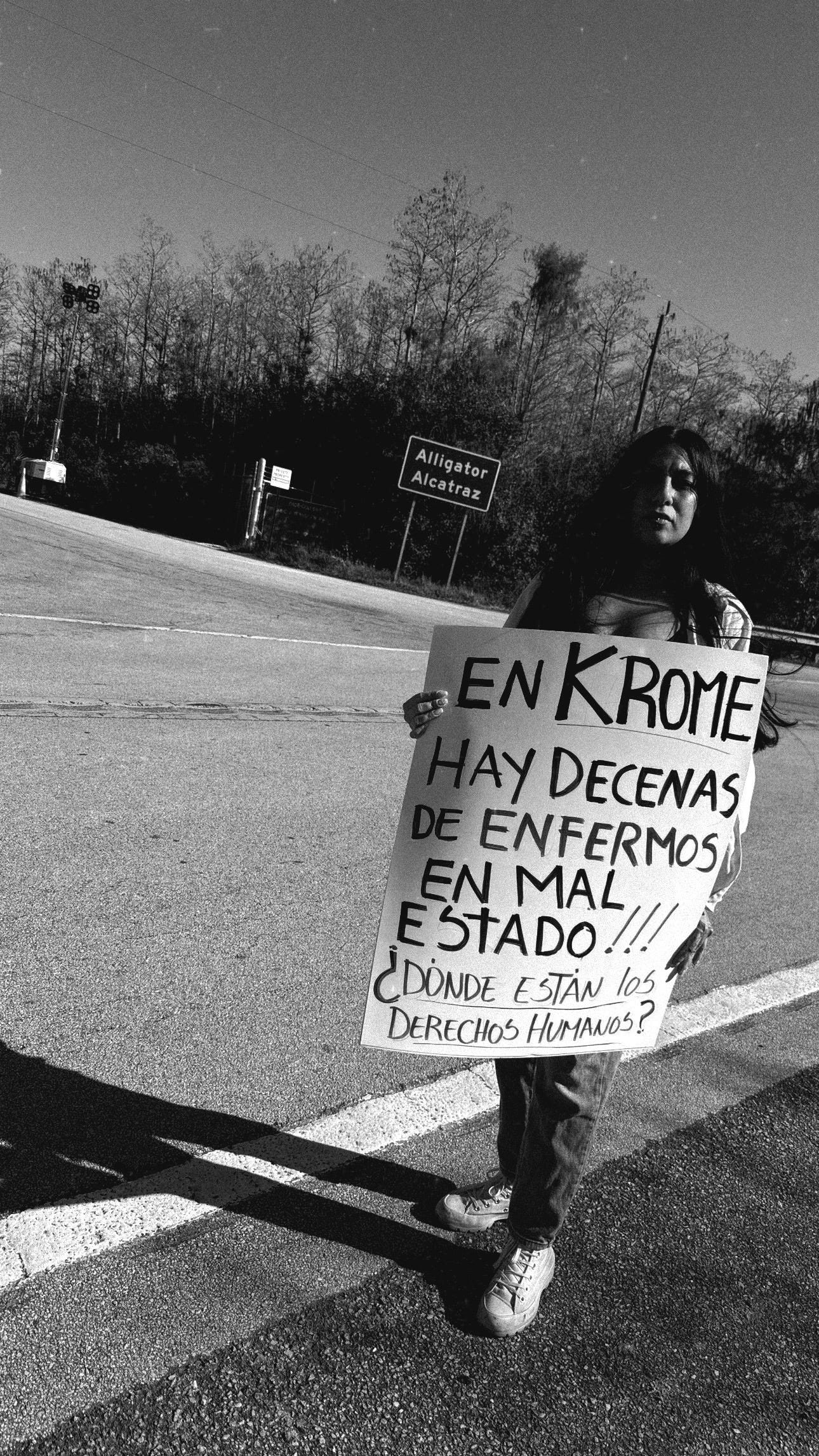

Since entering ICE custody in November, Denis has experienced multiple medical emergencies, predictably, and with increasing severity. His fiancée, Janet, says Denis suffers daily symptoms inside detention: blood sugar readings above 450 mg/dL, chest pain, confusion, neurological distress. He asks for help. He is denied.

Medical attention, she says, comes only after he collapses.

Denis has been hospitalized twice. Each time, he was treated just long enough for his blood sugar to be brought down, then returned to detention without any serious investigation into why his body keeps failing under these conditions. There has been no sustained monitoring. No adjustment to the environment triggering these crises. No continuity of care. Just stabilization and return. Stabilization and return. Over and over again.

This is not medical treatment. It is damage control.

Every day, Janet says, they wake up preparing for another collapse. Every day, Denis watches other detainees collapse around him. Every day, he wonders whether his body will hold out long enough to reach his next court date. That fear is not abstract. It is lived, hourly, in a system that treats chronic illness as an inconvenience rather than a responsibility.

When ICE detains someone, it assumes total responsibility for their health. That responsibility is not conditional. It does not begin only after a person loses consciousness. It includes prevention, monitoring, communication, and care. When those obligations are ignored, custody becomes cruelty.

The silence surrounding Denis’s condition makes that cruelty sharper. His family has gone days without communication. They have not received clear explanations about his care or his repeated hospitalizations. ICE has offered no public accounting of why a known insulin-dependent diabetic is being allowed to deteriorate repeatedly under its watch.

When the same authority controls a person’s body and controls access to information about that body, silence is not neutral. It is power being used to shield itself.

Amnesty International has intervened, issuing an urgent action calling for Denis’s immediate release and warning that denying proper medical care to an insulin-dependent detainee places him at risk of serious harm and death. Amnesty’s language is careful, but unmistakable. This pattern is known. The outcome is predictable. Delay is the danger.

There is a cruel symmetry to Denis’s story. In Cuba, the state silenced his work. In the United States, the system is silencing his body. Different governments. Different rhetoric. The same result: a man rendered vulnerable by the very authorities claiming control over his fate.

Denis Cabrera Rodríguez is not asking for special treatment. He is asking for insulin, appropriate food, medical care that does not wait for collapse, and release from conditions that are demonstrably making him sicker. If ICE cannot safely detain people with chronic medical conditions, then detention itself becomes the harm.

And this is where responsibility shifts outward.

If you are reading this, you can help.

You can amplify Amnesty International’s urgent action demanding Denis’s release. You can call and write to ICE, to DHS oversight offices, and to your members of Congress, demanding immediate medical release for detainees with life-threatening conditions. You can share Denis’s story publicly, loudly, and repeatedly, because silence is what allows this cycle to continue. You can support independent journalism that documents these cases before they disappear behind bureaucratic language and locked doors.

Most of all, you can refuse to accept “stabilized” as a synonym for “safe.”

Denis is still alive.

That should not be treated as luck.

It should be treated as a responsibility — one this system is failing, every single day.

Janet Soto speaks with Chance Meeting. Click here for the full-length video.

Paid subscribers to Closer to the Edge make it possible to report these stories with care, depth, and accountability — and to keep pressure on systems that rely on silence to function.

How do we reach authorities in charge of detainees medical needs?

Where is he currently being held? Is there a detainee number we can reference?